Drawing without decoration: reflections from spark’s founder, stephen pimbley

Some of the most enduring lessons in architecture aren’t necessarily spoken. They arrive years later, in quiet clarity.

When SPARK’s founder, Stephen Pimbley, was a student at the Royal College of Art, James Gowan said something that he did not quite understand at the time.

“Ruskin Gothic disciple, but without the decoration on the flying buttress”

sTEPHEN was around twenty-four, and at the time, it seemed an almost baroque way of describing himself as a stripped-down modernist. It took HIM decades to realise he wasn’t talking about style — he was talking about morals, architectural and intellectual.

ARCHITECT JAMES GOWAN.

GOWAN WAS ALSO STEPHEN’S PROFESSOR AND STUDIO TEACHER.

Gowan was a kind man if you were a serious student. His meticulousness bordered on obsession, and that rigor left an impression on Stephen. At the time, he had just written a thesis on James McLaren, the Scottish Arts and Crafts architect about whom almost nothing had been written. Gowan championed the work, not because it was fashionable, but because it was genuine. That encouragement led to a scholarship. But more than the prize, it planted a seed: that quiet, original research rooted in the overlooked can make architecture richer.

Around the same time, Financial Times architecture critic Colin Amery visited Stephen’s degree show and published a piece about his work: “Art is the best route into architecture.” That line has stayed with him ever since. Stephen didn’t fully appreciate it then, but in retrospect, it read him better than he could read himself. His path has always been one of drawing before diagram, of story before system.

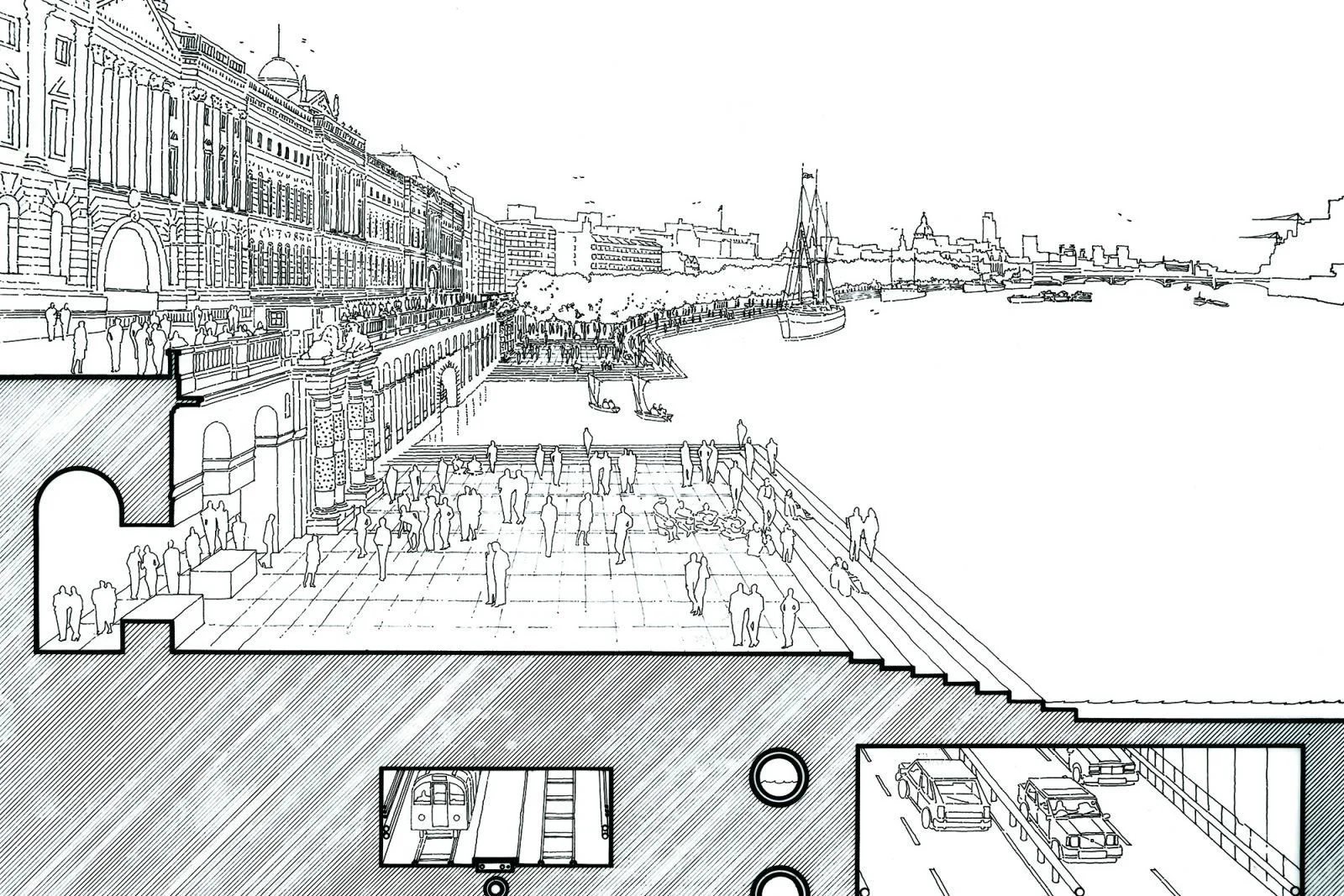

reimaginined North Thames Embankment as a park for people rather than a highway, drawing by stephen pimbley.

Later, when Stephen joined the Richard Rogers Partnership to work on the Royal Academy Rogers Foster Stirling exhibition, he assumed he was entering a world of components — of style defined by visible and legible mechanics. But what he discovered was Rogers’ unwavering belief in the city as architecture’s true subject. The layering of experience, the openness of a building to its street and its public, the spaces between things. this was where meaning lay. His buildings were not about technology; they were about access, both physical and visual.

That lesson became foundational for Stephen, and it continues to echo through the work he does now at SPARK. Whether we’re designing a riverfront regeneration in Shanghai or a bio-digesting bear made of rattan, the question is the same:

How can architecture act as an agent of urban accessibility?

How can it extend an invitation rather than assert a presence?

These are not rhetorical questions, they are design challenges.

Stephen has spent time living and working between London, Singapore, and Shanghai. This global experience is the reason he is drawn to the awkward spaces in cities: the leftover plots, the infrastructural margins, the places where architecture isn’t expected to thrive. These are the places where he feels design can be most generous, most surprising. His projects are sometimes playful, sometimes strange, but they are always civic in intention.

When Stephen was young, his father worked in New York. He was lucky to spend time in the city and continues to wonder at its history of scale, its speed, the exhilarating friction of it all. He considered studying in the U.S., but the Royal College of Art came calling, and with it, Gowan and his buttress without ornament. It’s only now that he understands he has spent much of his career sketching that buttress: sometimes pink and inflatable, sometimes woven and rural, but always trying to hold something up — community, delight, access.

Architecture has always been a way for Stephen to reconcile the formal with the informal, the serious with the surreal. He still believes — perhaps naively — in the power of public architecture to change how we live together. that’s what he tries to pass on, whether in the studio or through the work itself: that rigour doesn’t require decoration, and accessibility doesn’t preclude imagination.

Some riddles take decades to unfold. He is still trying to answer James Gowan’s.