THE ARCHITECTS JOURNAL “BRIGHT SPARK”

Non-disaster-related pro bono work by an English architect in Asia? Fee free design work is not often heard of beyond disaster relief or other situations of pressing humanitarian need – even at the best of times. Should one expect to hear about it during some of the worst? And what’s more, with a bank as the client?

Coloured by the shades of the Alsop and Archial brands, the 10-year history of Spark (formerly Sparch) is a picture book of the turbulence that can gurgle at the big-business end of the architectural industry. It’s also a straightforward tale of a very successful venture into Asia from the UK. Today’s Spark is an international architecture and design consultancy with its largest office in Beijing –an honour previously held by its Singapore branch. Spark’s portfolio is heavy with large-scale work for powerful clients, such as Singapore’s CapitaLand and Chinese development entities. Times aren’t so bad for Spark. In fact, they seem to be very good. It was feasible, therefore, for Spark co-director Stephen Pimbley to accept an invitation from Thailand’s TMB Bank to provide free design services for a charitable project. Spark previously had little connection with Thailand, being active there only with a minimal amount of unbuilt work. A feature on Spark in Thai magazine art4d and a personal connection between the editor and the head of the bank’s corporate communications division led to the invitation. The aims of the intended project ‘touched a nerve,’ says Pimbley. TMB Bank (formerly known as the Thai Military Bank and now serving non-military customers) has what appears to be an intense and sensible approach to its corporate social responsibility activities.

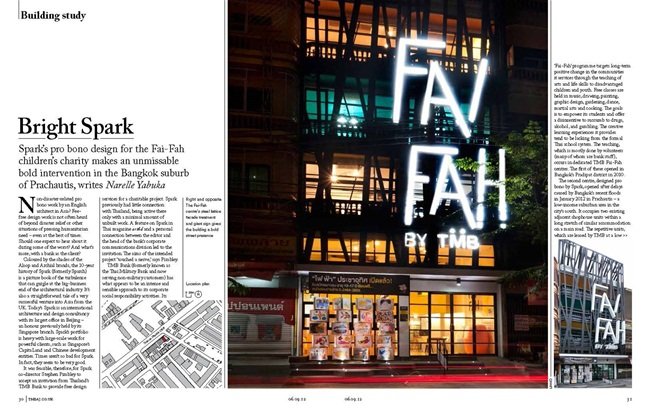

Its ‘Fai-Fah’ programme targets long-term positive change in the communities it services through the teaching of arts and life skills to disadvantaged children and youth. Free classes are held in music, drawing, painting, graphic design, gardening, dance, martial arts and cooking. The goals is to empower its students and offer a disincentive to succumb to drugs, alcohol, and gambling. The creative learning experiences it provides tend to be lacking from the formal Thai school system. The teaching, which is mostly done by volunteers (many of whom are bank staff), occurs in dedicated TMB Fai-Fah centres. The first of these opened in Bangkok’s Pradipat district in 2010. The second centre, designed pro bono by Spark, opened after delays caused by Bangkok’s recent floods in January 2012 in Prachautis – a low-income suburban area in the city’s south. It occupies two existing adjacent shophouse units within a long stretch of similar accommodation on a main road. The repetitive units, which are leased by TMB at a low what goes on inside should have some sort of expression on the outside.’ The facade screen, it turns out, was developed from children’s drawings and ideas about ladders and progression. The top of the screen folds back over a roof deck, where a garden is yet to be installed. As one of the most costly items in the renovation, as well as being technically unnecessary, its adoption would seem to say a great deal about TMB’s commitment to the project.

Pimbley felt that a white-box design would be an inappropriate response to the spirited workshop sessions and the energy of the children he encountered. The many brightly coloured drawings they produced, and one drawing in particular of Dorothy’s yellow brick road, prompted him to apply colour liberally and in a way that would encourage movement up through the interior. ‘Children aren’t afraid of using fantastic primary colours, because they’ve not been conditioned with all this nonsense about being polite,’ says Pimbley. ‘I wanted to use that colour.’

The word ‘ fai ’ translates as ‘electric’ or ‘spark’ (hence the yellow). ‘ Fah ’ means ‘blue’ – the corporate colour of TMB Bank. The blue paint specified by Spark diverges notably from the bank’s corporate hue and the apparent avoidance of blatant branding (beyond signage) was a sensitive move. Even with the central party wall demolished, the small floor plates of the units virtually predetermined their planning with a singular programmatic function per level. A sprung floor on the fourth level accommodates dance and martial arts classes. An art studio fills level three. A library and meeting room occupy level two. The ground level is a flexible space referred to as the ‘living room’, which connects to a small rear courtyard.

A ‘floating’, angular mezzanine level contains a gallery. Pimbley hopes artwork will be hung within and beneath it. A moulded sense of space and the triggering of imaginations was his aim. Robust, shimmering epoxy-coated yellow paint has been applied to the living room floor, the mezzanine gallery, and the staircase. A yellow-painted ‘utility stick’ – a new block of storage and bathroom spaces – has been plugged into the rear of the centre. Its surprisingly bold, anti-contextual surface treatment of yellow paint and circular motifs (including windows) seems jarring. Yet, once again, when you consider that the target audience consists of disadvantaged kids, the childish quality of the bubble motif is apt. An exaggerated, cartoonesque quality also emanates from diagonal internal mullions, boldly shaped balustrades and clusters of black cylindrical pendant lighting. Simplicity is further communicated by the necessarily robust, affordable finishes and detailing throughout. There are some sophisticated moments at Fai-Fah Prachautis –such as the moulding of space in the gallery and living room. There is also plenty that’s straightforward in design terms; over-simplified even.

But is the design ‘under-cooked’?

I would say ‘no’, considering that the centre was built on a budget and is skewed toward selling ideas to kids – ideas about imaginative engagement, creative output, self worth, and future possibilities. Indeed, considering how the workshop approach used by Pimbley aligns so beautifully with the Fai- Fah programme’s overall aims, the bubbles and ladders are well placed; they have surely generated feelings of empowerment and legendary schoolyard stories among their ‘authors’. With classes being heavily oversubscribed just months after the centre’s opening, the children of Prachautis seem to appreciate and need the service. TMB and its staff are certainly investing considerably in them. It comes as something of a surprise that banking-related paraphernalia is nowhere to be seen in the centre – not even as much as a money box graces the interior When it’s their time to apply for credit cards and mortgages, one expects that the kids will nevertheless think of TMB. The scale of the bank’s investment in its Fai-Fah centres, however, suggests that broad-based community strengthening (rather than gaining afew additional customers) is its goal. And the returns for Pimbley? He reflects on the job as an experience that recharged his batteries.