Beyond Buildings: Architecture as a Catalyst for Social Innovation

Architecture, at its best, is a social act.

They are modest endeavours by scale but ambitious in spirit. They are speculative, self-initiated, and often materially light. Yet they carry a serious intent: to engage with real issues that sit outside the usual client brief food waste, sanitation, care for the elderly, ecological degradation, and the right to public joy.

Projects like Big Arse Toilet, BARE, 3 Little Pigs, HomeFarm and Beach Hut were never meant to be trophies on a shelf or showpieces for awards. They were conceived as probing ways to test ideas about sustainability, community, and the human condition at a time when architecture risks becoming increasingly disconnected from the people and environments it's supposed to serve.

Big arse toilet, india.

The Big Arse Toilet was conceived as a response to the serious issue of open defecation in parts of the developing world, serving as both a symbol of dignity, privacy, and sanitation rights, and a functional solution that generates positive outcomes beyond merely solving the issue. Inspired by public health data and architectural interventions in neglected spaces, its exaggerated, cartoonish form embraces deliberate absurdity to encourage open discussion of otherwise difficult topics.

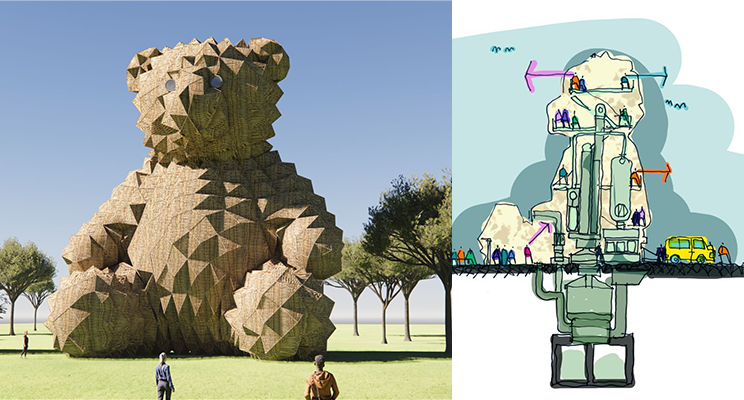

BARE(BIO-ANAEROBIC-RUBBISH-EATER) in the works.

BARE (Bio-Anaerobic-Rubbish-Eater) addresses the problem of food overproduction and the methane-heavy waste it creates. Designed in the form of a bear, it serves as both a functional solution and a storytelling device, proving that environmental messaging can be compelling, memorable, and even endearingly playful.

3 little pigs

3 Little Pigs, the familiar fable takes an unexpected ecological turn. This project emerged from research into industrial pig farming and its catastrophic environmental footprint, particularly the practice of flushing untreated pig waste into freshwater systems, resulting in eutrophication: excess nitrogen and phosphates on lakes and rivers that leads to algal blooms that deplete oxygen and kill aquatic life.

SPARK’s Three Little Pigs visualises the consequences of scale and disconnection, repurposing food-chain waste to reveal systems out of balance. The pigs, designed as spectral, gas-filled sculptures, embody our appetites, blind spots, and complicity in environmental harm.

If BARE is about public engagement with food waste through humour and affection, 3 Little Pigs is its darker cousin: cautionary, murky, a story of accumulation turned toxic. Yet it is still rooted in flows, thresholds, boundaries breached and how waste can be used to benefit the community.

homefarm, singapore.

HomeFarm proposes an intergenerational housing model in suburban Singapore that links aging residents with younger urban farmers in a mutually beneficial ecosystem, not only to grow food but also friendship and purpose. It grew from a very real concern about elderly isolation.

beach hut, east coast park, singapore.

The Beach Hut project, designed for Singapore’s East Coast Park, addresses both the crisis of ocean plastic and the rituals of youth seeking independence. Clad in shingles made from reformed HDPE2 plastic waste, their textured, scale-like surfaces recall the geometry of Casuarina seeds, usually found scattered along the shore. More than shelters, the huts act as small public gifts, dignified retreats for young Singaporeans who pitch tents by the coast in search of solitude, space, and sea breeze.

What links these projects is a commitment to remain close to the ground materially, ethically, and metaphorically. They resist architectural bravado in favour of precision, intimacy, and purpose, sitting somewhere between art, infrastructure, and design research. In a world where climate change, food insecurity, aging populations, and urban migration are met with too little imagination, such un-commissioned and underfunded initiatives play a vital role, creating their own gravitational pull outside the market or academy.

These works began not as solutions but as questions:

What if a toilet could be joyful?

What if a landfill could generate warmth?

What if a children’s tale could clean water?

They are a dispatch from the margins of architecture, where it meets the messy realities of everyday life. May they inspire others to design from conviction rather than compliance, and to remember that the smallest projects often pose the biggest questions.